At the School of Ideas

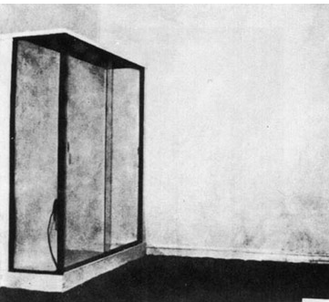

It seems society has a preoccupation with squares. From Malevich's squares to Mondrian's, to Yuri Pattison's re-framing of the traditional aesthetic "square" of the picture frame, the cuboid museum vitrine and shipping crate as parallel to the digital "square" - the photographic image, the computer screen - all framed by the sharp edges of right angles, to the literal town squares, the plateias or piazzas, traditionally centres for community-led discourse and interaction, it seems we humans always operate within "squares".

In some ways, this is what Jenny Marketou was getting at in her recent project, Red Eyed Skywalkers, Silver Series (2011), staged at the Kumu Museum in Estonia in an exhibition exploring networked cultures. Marketou installed silver metallic balloons both inside and outside of the museum space, each with tiny camera's attached to them and connected to nine screens displayed inside the museum. On the screens, images taken from the balloon feeds were then intermingled with found footage the artist had sourced from various web-portals - from youtube.com to wikileaks.com, depicting the wave of revolutions - namely, the Arab Spring - that had staged themselves in city squares.

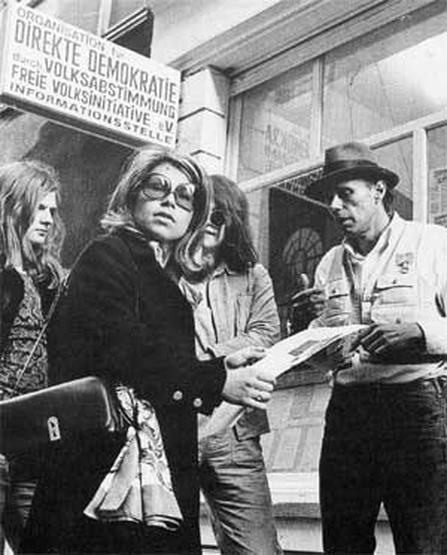

Marketou acknowledges that it was not only the physical square that had facilitated revolution - the square screens of mobile telephones, of youtube clips, of computer and television screens had also played a major role in the shaping of these political movements. In these movements, from Tunisia to Egypt, the "public square", that age-old community focal point had transitioned from the physical world into the virtual world in a fundamental way. One might call it a paradigm shift. Soon after, movements cropped up in Spain, with the Los Indignados movement that triggered a similar action in Greece, in which protestors took to their squares, and stayed there. Via the Internet, the two movements were in close contact with each other.

The movements in Greece and Spain started much earlier than the Zucotti Park movement that gave rise to Occupy - but in the end, the impetus for Occupy most likely came from the Arab world, passed into the Mediterranean, and through into the "mainstream" West. The format had been viral. From the "tent city" in Tahrir, to the tent cities everywhere, all facilitated - and operated - largely by online media. Nowadays, revolution is no longer national, but global.

But how successful might such movements be may very well depend on how well those squares designated as public are defended. And while protestors have been "lawfully" removed from such physical "squares", for example, with the St.Paul's occupation finally coming to an end, the internet is now becoming the territory upon which both political movements and the political forces currently in control are to stake their claim. As we have seen with SOPA and ACTA, and Anonymous's response to the increasing drive towards increased internet legislation, the battle for the public square has firmly gone virtual.

But how successful might such movements be may very well depend on how well those squares designated as public are defended. And while protestors have been "lawfully" removed from such physical "squares", for example, with the St.Paul's occupation finally coming to an end, the internet is now becoming the territory upon which both political movements and the political forces currently in control are to stake their claim. As we have seen with SOPA and ACTA, and Anonymous's response to the increasing drive towards increased internet legislation, the battle for the public square has firmly gone virtual.

Installation shot of Redeyed Skywalkers courtesy of Kalevkevad at Flickr

RSS Feed

RSS Feed