Andreas Fraser created a project that is called “Information room” (1998) in which she installed the archive of Kunsthalle Bern. Usually public doesn’t have an access to this archive. In this case ,“Information room” became a project about transformation the material in order to explore the relationship “between the act of making information accessible to the public and the transfer as symbolic action”.

At the beginning, Kunsthalle Bern was supposed to work in collaboration with Fraser. Instead, Fraser delivered only the idea and the whole project was conducted by the institution.

Nevertheless, the idea was to ‘displace, into the public space of the gallery, all the information that had been collected by the institution’. Basically the director of Kunsthalle saw it as an attempt to “invert the selective, directed, institutionally sanctioned presentation of pre-digested information which such ‘information rooms’ and related educational projects tend to display”. Whereas Fraser was talking about “Information room” as a public process.

Andrea Fraser’s description:

The director agreed to my proposal and, as a first step, moved the archive of the institution into the gallery, arranging it in appealingly haphazard and sort of post-minimal cubes of archive boxes on wooden pallets on the gallery floor. These boxes sat there like that for a much longer period of time than I supposed they would. Right away, people began opening up the boxes and going through them, pulling things out, putting them back-or not. I was actually quite surprised that the institution did not make any particular provision for insuring that the materials were not taken out or even taken away. While I wouldn’t have asked the institution to do that it was, I think, quite good interpretation of the process which the concept was intended to initiate. The intention was certainly to disorganise and derationalise the information presented by the institution. After a few weeks it really became a big mess. It was great. Apparently, people spent quite a bit of time looking through the material there. I was told that there were a few people who even came back regularly, sitting down for hours at the table(which was also haphazardly placed in the gallery) looking through box after box.

The programme I developed for the information room included installing the entire archive and the entire library in the gallery, along with as many of the posters as would fit on the walls. The thick was that all the books and archive boxes were to be installed with their spines to the wall, so that the visitors would have access to the material, they would not be able to pre-select what they pulled from the shelves. Meanwhile, the posters would be installed behind the bookshelves, so one would only be able to see them taking out the books. I wanted to make a Cageian information room where all information would be available, but access to it would be rendered arbitrary, accidental. But this argument was also supposed to provide a bit of protection of the archive which was supposed to be installed on the higher shelves. However, it took, I think, four or five months for these shelves to be installed. Various trustees and former directors of the institution, who apparently had secrets hidden in some of those boxes and were concerned about liability, began to protest. I can say that it was all out of my hands. The Cageian information room turned into a Cageian project as well!!"

Is the Internet a Space?

The other day a conversation turned towards the notions of "online" and "digital" and the question whether the Internet is a space or not. The person I was speaking to did not believe the Internet can be perceived spatially, while I took the opposing side. We often forget that the internet is not a purely virtual entity - there are physical spaces as well as networks that actually power this online "universe". To get a better idea, check out the visualization in the video below, when Sergey Brin, here speaking alongside Larry Page, co-founders of Google, presents a mapping of Google usage and networks in real time, which they actually use in Google's offices. Brin points out that fibre optic networks and satellites are absolutely necessary in facilitating the transmission of data between places.

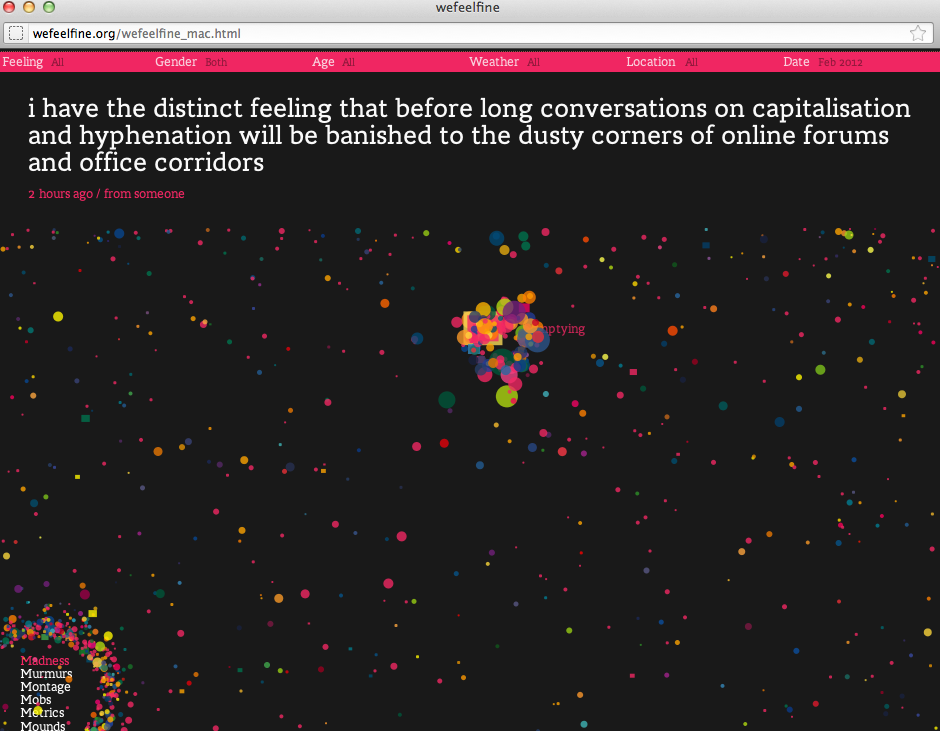

His 2006 work, We Feel Fine (2006), was an applet Harris created with Sep Kamvar. An applet that has been harvesting human emotions on the internet since 2006, it then organizes these harvested emotions via various interfaces. When you connect to the applet (shown below), a swarm of dots in various colours each represent different emotions. Below was a search for "all emotions" in February 2012. Clicking on one dot, the below quote came up. The visualization of individual utterances of people connected by feelings makes We Feel Fine, as Harris notes, an art project created by "everybody" and the coding to create the applet is available on the project website under the Creative Commons. S Somehow, We Feel Fine visualizes bodies in space, virtualized, but representative of bodies nonetheless. Of course, that would be most true in a search created specifically for the month and year you are searching, as you then exclude those "bodies" that no longer exist, either in the virtual or the physical world. The deceased, in other words, who are becoming a real pertinent issue in the debate surrounding the Internet realm. In fact, this month, new legislation that deals with what to do with the online accounts and profiles after someone dies has been tabled in Nebraska. This new legislation is an interesting one in that it proposes to include Facebook accounts into the deceased's estate plans - technically, their Facebook profile would then be rendered "property" . Would that then confirm that the Internet is being treated in "spatial" terms? Think about Second Life! In the end, the question still stands: is the Internet a Space? And saying that, what is the difference between "online" and "digital"? Looking at Harris's work, We Feel Fine touches on the distinction between "online" and "digital" in that "online" might be posited to be the virtual milleu - the format or the space - within which digital matter exists as form?

At the School of Ideas

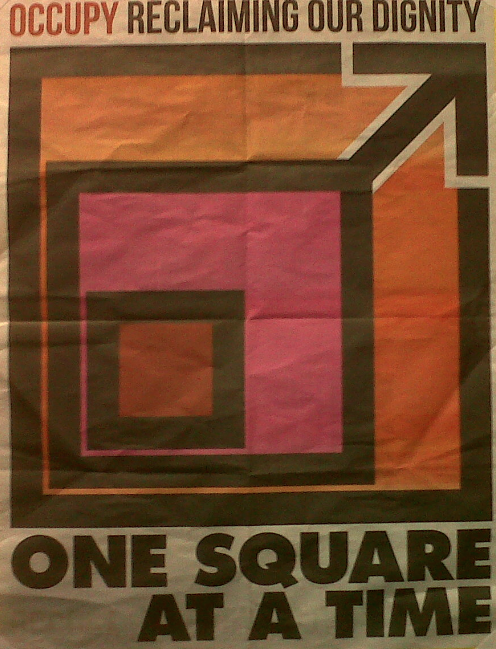

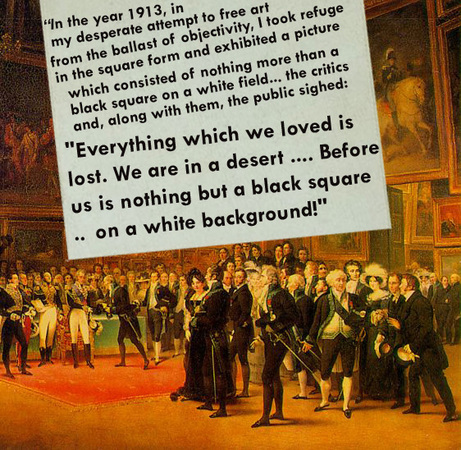

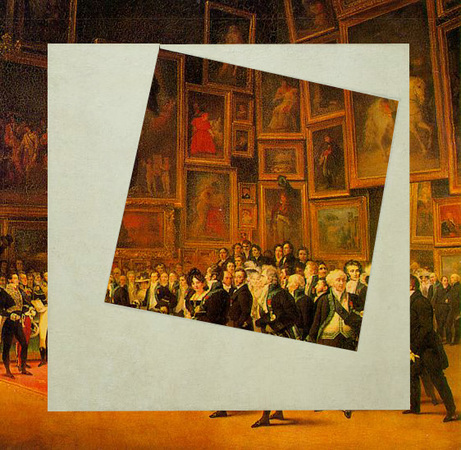

It seems society has a preoccupation with squares. From Malevich's squares to Mondrian's, to Yuri Pattison's re-framing of the traditional aesthetic "square" of the picture frame, the cuboid museum vitrine and shipping crate as parallel to the digital "square" - the photographic image, the computer screen - all framed by the sharp edges of right angles, to the literal town squares, the plateias or piazzas, traditionally centres for community-led discourse and interaction, it seems we humans always operate within "squares". In some ways, this is what Jenny Marketou was getting at in her recent project, Red Eyed Skywalkers, Silver Series (2011), staged at the Kumu Museum in Estonia in an exhibition exploring networked cultures. Marketou installed silver metallic balloons both inside and outside of the museum space, each with tiny camera's attached to them and connected to nine screens displayed inside the museum. On the screens, images taken from the balloon feeds were then intermingled with found footage the artist had sourced from various web-portals - from youtube.com to wikileaks.com, depicting the wave of revolutions - namely, the Arab Spring - that had staged themselves in city squares. Marketou acknowledges that it was not only the physical square that had facilitated revolution - the square screens of mobile telephones, of youtube clips, of computer and television screens had also played a major role in the shaping of these political movements. In these movements, from Tunisia to Egypt, the "public square", that age-old community focal point had transitioned from the physical world into the virtual world in a fundamental way. One might call it a paradigm shift. Soon after, movements cropped up in Spain, with the Los Indignados movement that triggered a similar action in Greece, in which protestors took to their squares, and stayed there. Via the Internet, the two movements were in close contact with each other.

The movements in Greece and Spain started much earlier than the Zucotti Park movement that gave rise to Occupy - but in the end, the impetus for Occupy most likely came from the Arab world, passed into the Mediterranean, and through into the "mainstream" West. The format had been viral. From the "tent city" in Tahrir, to the tent cities everywhere, all facilitated - and operated - largely by online media. Nowadays, revolution is no longer national, but global.

But how successful might such movements be may very well depend on how well those squares designated as public are defended. And while protestors have been "lawfully" removed from such physical "squares", for example, with the St.Paul's occupation finally coming to an end, the internet is now becoming the territory upon which both political movements and the political forces currently in control are to stake their claim. As we have seen with SOPA and ACTA, and Anonymous's response to the increasing drive towards increased internet legislation, the battle for the public square has firmly gone virtual.

Installation shot of Redeyed Skywalkers courtesy of Kalevkevad at Flickr

The room, the empty space, the frame - bodies in space.

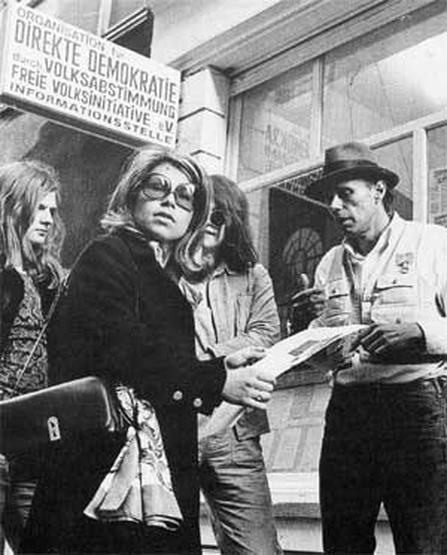

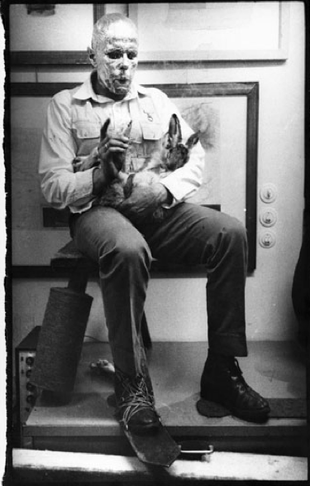

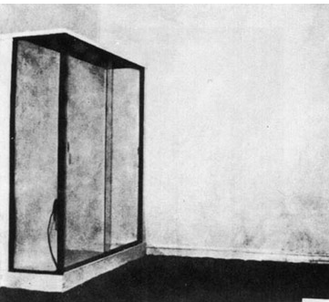

Staged at Documenta 5:100 Days of Inquiry in 1972, Joseph Beuys' Bureau for Direct Democracy consisted of a space with a sign identifying the name of the installation hung outside (see below). For 100 days, Beuys instigated debates with gallery visitors on political, artistic and social issues. Apparently on the last day he fought a Boxing Match for Direct Democracy with one of his students. The notion of artists performing in space, or the artist constituting the work recalls Gilbert and George, when, in 1970, they painted their faces bronze, wore their sharpest suits, and stood on a platform in the Nigel Greenwood Gallery, singing to a recording of Flanagan and Allen’s Under the Arches for eight hours a day. Five years earlier, Beuys had applied gold leaf to his face, stuck on by honey he had bored over his head, for a performance he titled How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965), witnessed only by a photographer and a film crew. In an interview, Beuys noted of the action: “This seems to have been the action that most captured people’s imaginations. On one level this must be because everyone consciously or unconsciously recognizes the problem of explaining things, particularly where art and creative work are concerned, or anything that involves a certain mystery or question. The idea of explaining to an animal conveys a sense of the secrecy of the world and of existence that appeals to the imagination. Then, as I said, even a dead animal preserves more powers of intuition than some human beings with their stubborn rationality.The problem lies in the word ‘understanding’ and its many levels, which cannot be restricted to rational analysis. Imagination, inspiration, and longing all lead people to sense that these other levels also play a part in understanding. This must be the root of reactions to this action, and is why my technique has been to try and seek out the energy points in the human power field, rather than demanding specific knowledge or reactions on then part of the public. I try to bring to light the complexity of creative areas.” - Joseph Beuys, courtesy of OrdinaryFinds.What links the two performances is the artist activating space using their own body, thus changing the awareness of space itself and often, the perception of the bodies in space. Going back to Bureau for Direct Democracy, Beuys made a point of curating bodies by framing a space as a place for interaction, debate and discussion. Yves Klein touched on this in 1958, when, for an exhibition at Galerie Iris Clert, he presented The Void (Le Vide) - a bare, white gallery space with nothing else inside. The audacity of showing an empty space as art, perhaps was a challenge to literally Leap into the Void, a reference to Klein's infamous 1960 work, and challenge ones own preconceptions of what constitutes art.

Here the manipulation of bodies in space suggests that it is not the space the creates content, but those within it. As Beuys suggest, such spaces might even contribute to the creation of direct democracy. Perhaps this is what Malevich was thinking about when he started painting black and white squares. Maybe that's what protesters have been thinking about more recently, with the Arab Spring and the Occupy movements. Space is an important thing. It can be a very political thing. And as Occupy London has been officially evicted from St. Paul's, physical space is becoming such a rarity, one might wonder where such bodies might interact?

Relating to the Science of Space, from the White Cube perspective

the infinite (void)

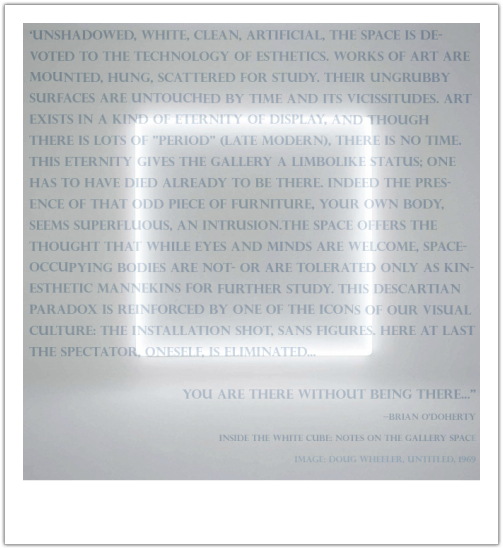

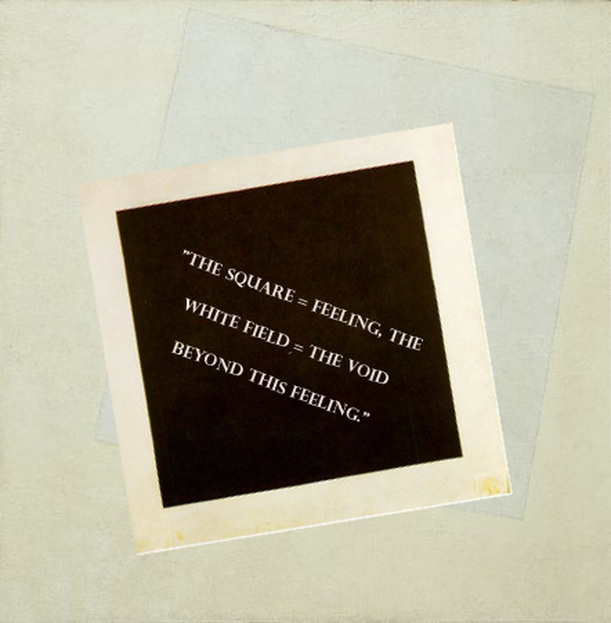

Doug Wheeler's latest show at David Zwirner presents new work, SA MI 75 DZ NY 12 (2012), an "infinity environment" which plays on the materiality of light to create a physical experience of infinite space, something the artist has explored throughout his career. The Wheeler piece is visually the antithesis of the Miroslaw Balka installation at the Tate Modern's Turbine Hall in 2009, in that Balka played on the absence of light by using a heavy, industrial material - steel - in an industrial-sized space (ex-industry), to construct a dark cavern - the opposite of the white cube. The two works depict "white" and "black" space, both acting as notions of the "void". Walking inside Balka's installation was not unlike how someone described Wheeler's show in New York, in that once inside the space, you didn't know where it started or ended - unless of course you looked towards the natural light source - behind you most probably. (Echoes of Orpheus and Eurydice here, not to mention the Cave Analogy). The binary nature of the two exhibits - Wheeler's pure, white space, and Balka's black abyss, somehow recalls Kasimir Malevich's Suprematism Manifesto, in which he declared:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed